The Rio de la Plata basin, also known as the River Plate Basin in British text books, is the largest fluvial system in Argentina. It is also the second biggest basin in South America, right after the Amazon Basin. It is an exorheic river system which drains a huge portion of Argentina's territory. This territory includes the northeastern, a part of northwestern, and central Argentina, as well as Uruguay, Paraguay, and the southern portion of Brazil.

The Rio de la Plata basin is drained by a complex network of rivers, of which the Parana and Uruguay River are the most important ones. These two rivers confluence into one another to form the Rio de la Plata, which is the widest river in the world; as a matter of fact, it is really an estuary, with 190-km wide at the point where it flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

The Parana River originates in southern Brazil as Paranaiba River, which becomes the High Parana after it receives the waters of an eastern tributary, the Tiete River (still in Brazil). As it flows southwards, the High Parana makes the international border between Argentina and Paraguay. At this point, another eastern tributary flows into it; the Iguazu River, which makes the Iguazu Falls just as it flows into the northeast of Argentina. Then the High Parana turns westward, flowing in this direction for about 400 km.

Right at the bend where it turns south, the High Parana receives its main tributary, which is the Paraguay River that flows from north to south across the nation of Paraguay. At this meeting point, it becomes the Middle Parana, which runs from north to south. Having received small tributaries, the Middle Parana gets about 50% of the rain water of the Northwest of Argentina through the Salado River, which flows into it at the level of the city of Santa Fe, in the Province of Santa Fe.

As it takes an eastward course, turning around the big bend of the province of Entre Rios, it becomes the Low Parana, also called the Parana River Delta, where it gets fluvial water from the Uruguay River. When these two important water courses flow into one another, they form the Rio de la Plata (River Plate).

“Fluvial”, from Latin Fluvium, which means ‘river’. “Exorheic” means ‘draining towards the sea’.

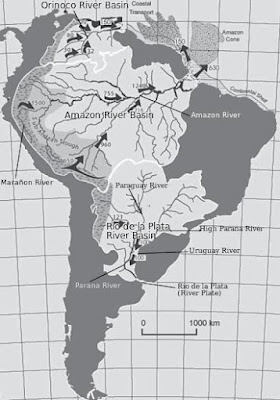

Below, a map of South America showing the rivers that make up the Rio de la Plata Basin